Strict Standards: Only variables should be assigned by reference in /home/noahjames7/public_html/modules/mod_flexi_customcode/tmpl/default.php on line 24

Strict Standards: Non-static method modFlexiCustomCode::parsePHPviaFile() should not be called statically in /home/noahjames7/public_html/modules/mod_flexi_customcode/tmpl/default.php on line 54

Strict Standards: Only variables should be assigned by reference in /home/noahjames7/public_html/components/com_grid/GridBuilder.php on line 29

Now, not only is Cafferkey back in the hospital with a rare relapse of the deadly virus, but she's gotten worse.

London's Royal Free Hospital announced Wednesday afternoon that "Cafferkey's condition has deteriorated and she is now critically ill."

The hospital didn't elaborate on the news about the Scottish nurse, who last year became the first person diagnosed with Ebola in the United Kingdom. But it's not a good sign, coming five days after the same medical facility confirmed Cafferkey had been transferred there from Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in Glasgow "due to an unusual late complication of her previous infection by the Ebola virus."

That day, the Royal Free Hospital indicated that Cafferkey was in "serious condition" and being treated in a "high-level isolation unit."

"Sad to hear of deterioration in Pauline Cafferkey's condition," UK Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt tweeted. "Thoughts & prayers with her & wonderful team looking after her @RoyalFreeNHS."

Since her January discharge, Cafferkey has been out and about, including receiving a Pride of Britain award late last month and paying a visit to 10 Downing Street, where pictures showed her with the prime minister's wife, Samantha Cameron.

Last week Dr. Emilia Crighton, director of public health for the National Health Service for Greater Glasgow and Clyde, insisted that the risk of the 39-year-old Cafferkey inadvertently passing on Ebola to anyone else was "very low."

"In line with normal procedures in cases such as this, we have identified a small number of close contacts of Pauline's that we will be following up as a precaution," Crighton said.

Went to Sierra Leone during Ebola outbreak

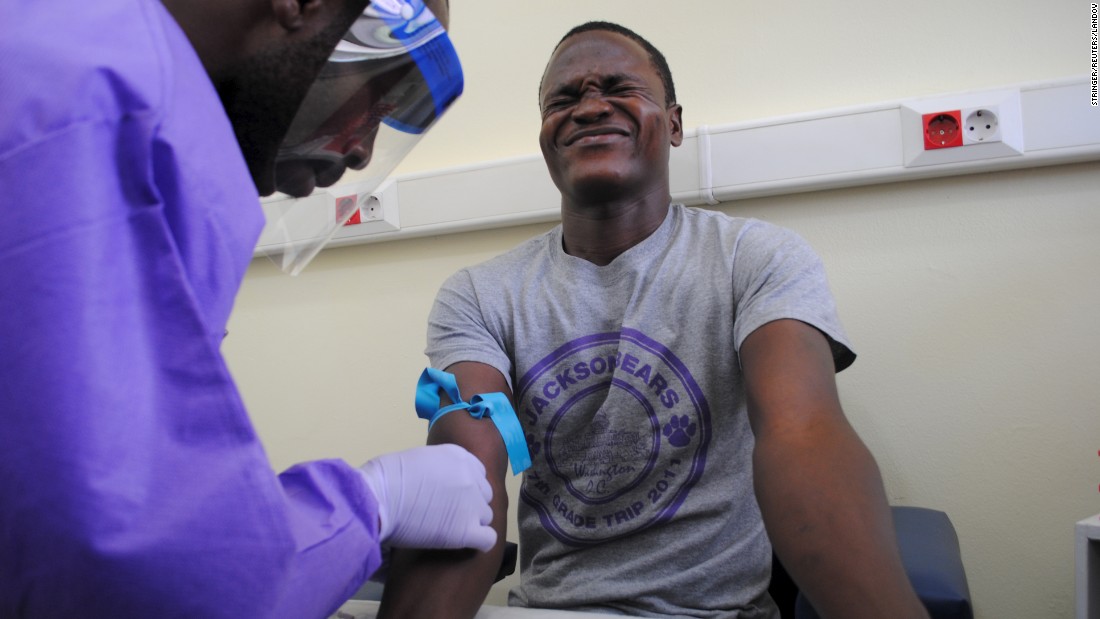

Like many other volunteers, Cafferkey had gone to West Africa knowing the dangers there. The Ebola virus had spread like wildfire, ultimately killing more than 11,000 people and infecting some 28,000, according to the World Health Organization.

Yet that harsh reality didn't stop the public health nurse in Scotland's South Lanarkshire area from being part of a 30-person team deployed by the UK government to work in Sierra Leone with Save the Children.

She and other health care workers would later be credited with playing a significant part in corralling and ultimately ending the devastating outbreak.

But, as Cafferkey learned, it came at a cost.

She fell ill shortly after touching back down on UK soil. Her Ebola diagnosis came next, followed by intensive treatment at the Royal Free Hospital. That facility has an isolation unit tended by specially trained medical staff and a tent with controlled ventilation set up over the patient's bed.

Her road to recovery wasn't always smooth. The Royal Free Hospital at one point noted that her condition had "gradually deteriorated over ... two days" and that she was then critical.

Cafferkey, though, managed to rebound and weeks later was allowed to go home.

Agency: 58 had contact with symptomatic nurse

She had good reason to celebrate September 28. That night she was honored at the Pride of Britain awards, a star-studded event (with this year's celebrities including soccer star David Beckham and Rupert Grint of "Harry Potter" fame) honoring good deeds around the country, spokeswoman Elizabeth Holloway told CNN.

The next day, Cafferkey joined other honorees at the Prime Minister's residence.

Less than a week later, on October 5, she went to a doctor in Glasgow because she felt sick, said a spokesperson for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, who was not named per policy. Cafferkey was sent home, only to be admitted the next day to Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in the Scottish city.

Holloway said no one associated with the Pride of Britain awards is being monitored for possible Ebola, because Cafferkey wasn't showing any signs of illness at the time. Ebola only spreads when there's direct contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person who is displaying symptoms of the disease.

In a statement, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde said that health authorities have identified 58 people who had been in close contact with Cafferkey since she became symptomatic. Forty of those who'd had direct contact with her bodily fluids were offered an Ebola vaccine; 25 of them accepted while 15 declined, according to the health agency.

And yes, tests earlier this year indicated the nurse wasn't showing signs of Ebola. But that doesn't mean that traces of the virus can't linger -- if not in the blood, then perhaps elsewhere in the body.

Her relapse is also proof that the Ebola fight isn't totally over, one week after WHO reported the first week since March 2014 with no new cases.

New death 7 weeks after Liberia declared Ebola-free

U.S. doctor had traces of Ebola in eye months later

According to the WHO, Cafferkey was then and is still the lone Ebola case in the United Kingdom.

Her relapse does not represent "a new case of Ebola (but rather) is a complication of her previous illness," Scotland's chief medical officer said Friday. It's a rare thing, but not necessarily unprecedented.

American doctor Ian Crozier was treated for Ebola in Atlanta last year and declared free of the virus in his blood.

But less than two months after being discharged, Crozier started experiencing problems with his vision, and doctors were stunned to find traces of the virus in fluid from his eye.

Despite the presence of the virus, samples from tears and the outer eye membrane tested negative, which meant the patient was not at risk of spreading the disease during casual contact, the hospital said at the time.

Crozier received steroids and an antiviral agent, and his eye gradually returned to normal. His case prompted a warning to doctors to watch Ebola survivors for eye problems.

CNN's Eve Parish, Debra Goldschmidt and Tim Hume contributed to this report.

Strict Standards: Only variables should be assigned by reference in /home/noahjames7/public_html/modules/mod_flexi_customcode/tmpl/default.php on line 24

Strict Standards: Non-static method modFlexiCustomCode::parsePHPviaFile() should not be called statically in /home/noahjames7/public_html/modules/mod_flexi_customcode/tmpl/default.php on line 54

Find out more by searching for it!